Collaboration and Critique with an Anti-Bias Foundation: Designing Classroom Murals

“I’ve always wanted to have a classroom mural created by kids.”

I honestly cannot remember what my co-teachers and I were talking about before this came out of my mouth, but from that point on, it was inevitable – we would have a mural. We actually ended up with three, one of which was a mural installed at a bus stop shelter across the street from Hilltop at our Queen Anne location. As my co-teachers and I talked about it, our hopes for our students began to crystallize, coming from the classroom values we had identified for ourselves earlier that year: community, competence, and open-mindedness.

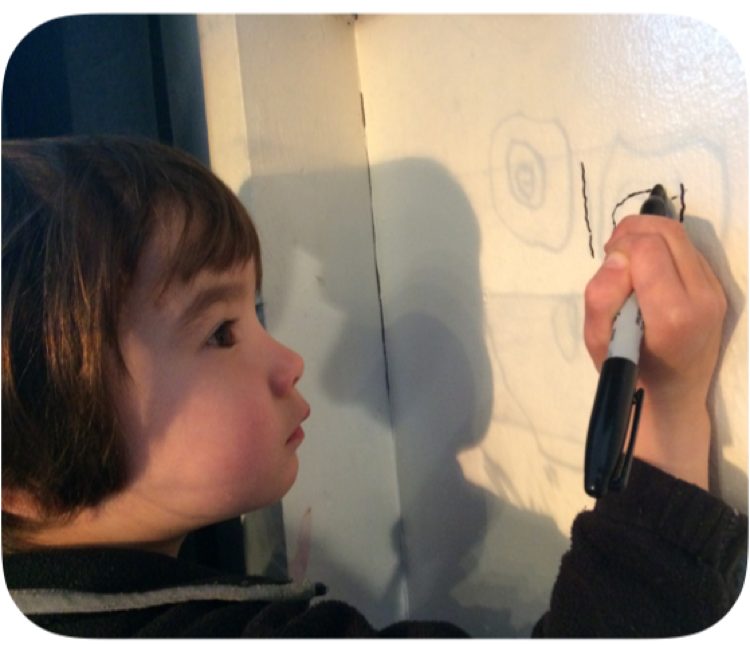

Depending on your upbringing, drawing on walls could be either welcomed activity or be seen as a somewhat of a taboo. I definitely ended up in trouble at least once for drawing on my walls! For a young child, drawing on different surfaces can be an exploration of what the rules of their environment are as well as promoting children’s visual/spatial intelligence, sense of self-worth as they impact their space, and aids in their development of creativity for lifelong success. A mural can create a sense of belonging and ownership, with a real personal stamp on a place, and the knowledge that you had a hand in making it more beautiful, more interesting.

In my classroom this year, more so this year than in any in recent memory, there was a tension between group needs and individual needs. While this tension is expected, we were feeling it with a group that had more intense emotional needs than previous groups. As my team discussed ways we can mitigate this, we decided that perhaps collaborating on a mural would create a natural yet supported opportunity to feel this tension and practice working in it. There would be times the group would have to come together and times that each child would make their choices on their own. To introduce this into the classroom, we decided to frame this idea as an art project based in beautification and belonging.

In my classroom this year, more so this year than in any in recent memory, there was a tension between group needs and individual needs. While this tension is expected, we were feeling it with a group that had more intense emotional needs than previous groups. As my team discussed ways we can mitigate this, we decided that perhaps collaborating on a mural would create a natural yet supported opportunity to feel this tension and practice working in it. There would be times the group would have to come together and times that each child would make their choices on their own. To introduce this into the classroom, we decided to frame this idea as an art project based in beautification and belonging.

Through intentional and reflective teaching practice, anti-bias education can show up in all developmental areas and in all academic subjects. Everything we validate or discourage with our children is a message to them about what we value as a culture, as a family, as an individual they love and admire. And because children are natural born scientists and observers, they are constantly gathering that data of what it means to be in community. We grownups need to be aware of that because we are helping guide the norms they will live by. This story is about a focused exploration we took as a classroom into murals, street art, and mediums for social change. What started as an exploration of art, turned into an exploration and deep dive into questions like:

- How does a child’s artistic development play into their identity development?

- How does their sense of aesthetic interact with their development as citizens and community members?

- As grownups in their lives, how can we leverage their constant observation and evaluation of their environment to not only build up their own sense of belonging but also their desire to advocate for others’ belonging, especially when those others are different from them?

I hope this story inspires you to consider where else in your curriculum there is space to open up and re-evaluate how your values align with your learning goals for children and where your biases are showing up. I encourage you to pause before reading further and reflect on these questions – As educators, how can we use images and art to question and interrogate the world for our students? How, at the classroom and larger community level, can we use images and art as social change and expressions of what the community desires?

Is Graffiti Art?

Often, when we are thinking about anti-bias curriculum, we educators will focus on representation – the idea that our children need to see the many ways there are to be human so they can see themselves and better appreciate those different from them. This project was coming at from a different angle, however. We were centering ideas of beautification and belonging – it was more about who has the right or the support to create in a community. I could see it forming when we began trying to define what a mural was with the kids. We had talked about how a mural is basically a design on a wall and it was probably big. As we began to explore our neighborhood and notice what was on the buildings around us, the kids noticed the Henry murals around our neighborhood, the nearby climate justice mural, and definitely pointed out the graffiti as well. We teachers were a bit stumped at first. Sure, we knew of some graffiti that was “art.” But is a ‘tag’ art? Would it be confusing to call it a mural? With a teaching team that was entirely white and a group of children that were mostly white, what messages would be sending them if we didn’t celebrate this form of expression? After all, graffiti, which the dominate culture views as bad and destructive, is often associated with gangs, which are associated with Black people. The answers we gave our students was going to have bigger message about what kind of expression is valid, and who belongs.

So, we embraced the challenge, decided that we would not pre-determine the vocabulary, and took the question back to the kids as a chance to develop all of our skills in thinking critically and talking respectfully about what we like, what we don’t, why we feel that way, and what boxes society puts us into.

Children as artists & critics

From the beginning of the year, we educators had brought an intention to focus on techniques and skills, and to call out how our students use them intentionally and accidentally to create. Honoring the hundred languages of children – inspired by the schools of Reggio Emilia, Italy – we wanted to find opportunities for them to grow their set of tools, in order for them to be as fluent as possible in all the ways they express themselves. Simultaneously, maintaining an anti-bias lens let us support them in developing their identities as artists, and gave them ways to look at others’ art in respectful and analytical ways. A child could know, for example, that they prefer to work with big brushes for the texture and broad coverage. They can also know that other people prefer fine brushes or spray paint, and that’s fine. Artists make choices that make sense to them.

As educators, we had worked to develop a classroom culture where our students were self-aware about what they were drawn to, about how their art was improving and changing, and about how they could interrupt when they heard hurtful comments. We also found other ways to practice collaboration and perspective-taking. We arranged loose parts together, taking turns adding elements, and watching an idea evolve into something surprising. We made up group stories about the character sketches being developed for our classroom murals, which required flexibility on the artists’ part, as other people interpreted their creations in unexpected ways.

As educators, we had worked to develop a classroom culture where our students were self-aware about what they were drawn to, about how their art was improving and changing, and about how they could interrupt when they heard hurtful comments. We also found other ways to practice collaboration and perspective-taking. We arranged loose parts together, taking turns adding elements, and watching an idea evolve into something surprising. We made up group stories about the character sketches being developed for our classroom murals, which required flexibility on the artists’ part, as other people interpreted their creations in unexpected ways.

As they are exploring their creativity, children will look to their peers’ skills and results for inspiration and for comparison. Children evaluate each other constantly. It’s not unfamiliar to hear them debate about who is taller, who is faster? It happens with their art as well. Whose butterfly is more beautiful? Whose T-Rex actually looks like a T-Rex? Children have ideas about who is good at art and who isn’t. They have preferences for what is beautiful or interesting or ugly or scary. One of our main entry points in this exploration was supporting the kids in having respectful and thoughtful conversations about others’ work.

To practice critique, we examined photos of murals and graffiti in Seattle and from around the world, taken by teachers and families, making note of the “artist’s choices” we could recognize (colors, realism versus fantastical, size, etc). We noticed what we liked and what we didn’t – and, most importantly, why.

Some of the observations we heard were:

- “That one is more real than that one.”

- “They wanted to make it look their way.”

- “I think they wanted to draw it like it’s reflecting.”

- “This one with the cat is my style because it’s so beautiful. The one with the stars is not my style.”

- “I don’t like this one. It’s messy. And I don’t like this one. I think they did it really fast.”

- “I like this one because it has two octopuses. I don’t like the cat one because the cat is so mad. The octopuses are happy.”

Children as community members

Starting from the belief that our students are valuable community members now, as they are, with rights and responsibilities, meant that we were going to honor the tension between the individual and the group. This took us in a few directions. First, we asked our students to think beyond their own mural contribution to consider how it belonged with the others around it – how could we join them together in one world? Some background had been included already – a night sky on one end and a pink sky on the other. What would fit in-between? A sunset!

We took time, then, to individually study and paint sunsets: their colors, patterns, and lines. Using more photo inspiration from both online and personal collections, I offered very deliberate opportunities to talk about styles, techniques, and choices each child was making as they painted sunsets. Some observations from the kids included:

- “I twisted the brush to make suns.”

- “I used a striping technique for my sunset.”

- When asked by a friend why he was painting so slowly, a child responded: “So my colors don’t get on top of each other.”

- When talking about why they chose a thicker brush, a child told me: “It’s a better brush. I like thicker lines better.

Community Development Through Art

Moving from an individual to a group mindset included a class-wide vote on which colors to use for our sunset, in which order, and in which direction. Once that was decided, and sunset painting began, the children took great care of each other’s creatures already on the walls, painting slowly and carefully around them. They worked with calm bodies and focused minds. And, when it was all done, one child summed it up: “We all love it because we worked so hard on it!”

One way we built on our value of community was to take field trips, usually on the bus. Our regional transit organization has a program for people to apply to paint the panels of bus stops. Since this was a familiar part of our classroom life, we applied and were selected to paint a mural for the bus stop shelter across the street from the school – the bus stop that we waited at often for our field trips. A co-teacher picked up the panels and paint and brought them back to the classroom for us to work on. The bus shelter mural was designed by a small group of purposefully chosen kids who often were less outspoken about their art, as a chance to highlight their process. Talking to the kids about why and how to do it, they brought up that people going to that bus stop “need something to look at so they’re not bored waiting for the bus” and that “people will see it and might think it’s good and they might think it’s bad.”

Family Engagement

Throughout the year, we invest time and energy bringing families into the culture of the classroom. From the beginning, we communicate frequently through documentation and conversations about the values driving our work, the play-based and emergent curriculum we employ, and highlight how child-led exploration honors development and meaningful learning. By the time we were painting our murals, families knew the expectations and culture in our classroom. Since we were exploring belonging, it was important to us that families joined in on this venture too. Our community of artists expanded to include family members who joined in over the next few weeks to help paint the bus mural of an ocean and mountain scene. We saw adults and children all work to balance their own ideas with the group’s and cooperate across families as they found new connections. We saw children utilize their new skills both in painting and in supporting each other. And now, on the eastbound 31/32 bus route at the Nickerson St & Queen Anne Ave stop, you can have something interesting to look at while you wait.

Final Reflections

Embedded throughout this project was the idea of belonging. Who belongs and how do you know when you belong? How do we treat each other so that we all feel that sense of belonging? Which voices are heard and whose messages do we respect? As we compared graffiti as unsanctioned installations and murals as art that was allowed, we talked about who makes those choices about what is allowed and how it could feel to be left out. Especially since our classroom was populated mostly by white, affluent children we teachers need to build their skills around being curious and open-minded about differences, and courageous in the face of exclusion and hurtful comments. There was also an emphasis on understanding that artists make the choices for themselves, and that we may not always like it, but it still gets to be art in the world.

With this project, my co-teachers and I worked to bring to light our own biases and interrupt the harmful messages our students were getting about art, belonging, beauty. Anti-bias and anti-racist curriculum are not and cannot be an add-on. No matter the subject, we educators have a duty to prioritize equity and justice. Not just because it’s trending, but because our students are informed by our actions and inactions. What we say and what we omit. We can’t wait to make sure all the other boxes on the to-do list are checked off before we address racism and other harmful bias in our classroom. All of this work builds a foundation and a community culture that celebrates what each person brings, that doesn’t shy away from addressing hurt or conflict, and asks us to take care of each other. And pursuing projects like this one doesn’t wait for race to “come up.” It doesn’t wait for Black History Month. As educators, we start with the awareness that all aspects of our children’s development are influenced by their race, and that we need to plan for how they will explore what that means.

Reflection Question:

How can we address centuries of racism in art?

What are your assumptions about art?

What are your unexamined unconscious racist thoughts and beliefs about art, the usage of it, where it belongs, and what it should be used for?

How can we use conversations, books, plays, materials, and what’s happening in society to support the growth of children’s creativity and critical thinking skills in order to help children take action and ownership of their anti-racism work?

Hilltop Educator Institute collaborates regularly with change agents across North America, Europe and New Zealand to provide professional development opportunities in Greater Seattle through evening, half-day and full day workshops known as the Educator Discussion Series (EDS). Hilltop Educator Institute provides resources and support to educators, programs leaders, children’s advocates, and the community at large, in order to widen access and opportunity for all children. To study at Hilltop for a day, register for upcoming workshops, or learn more about our services, email Mike at institute@hilltopcc.org or visit us at www.hilltopcc.com/institute.