Teaching and Learning in Communities of Practice

by Sarah Felstiner, Curriculum Director, Hilltop Children’s Center

We often encourage young children to work together, play with friends, negotiate, and collaborate. One reason we do this is because we’re committed to helping children develop social skills…I think of this as the “prime directive” for children at this age: learning how to be in the world with other people. Children aren’t born knowing how to socialize, and they deserve opportunities to grow that skill. When they’re infants, everything is about them, and it should be. Then as they get older, they begin encountering other children, and finding themselves in unfamiliar and complex situations. I imagine their inner dialogue going a little something like this:

Child 1: I have a very strong idea about what should happen now.

Child 2: I also have a very strong idea. It is different from your strong idea.

Child 1: How inconvenient! What shall we do about our divergent ideas?

And so we prepare our environments and the flow of our days to encourage interaction and relationship building. We watch for moments of conflict, and consider them to be opportunities for social problem-solving. We carefully scaffold negotiations between children, and encourage them to generate solutions to their problems. “Let’s find an idea that everyone says ‘yes’ to” is a phrase I’ve uttered thousands of times, and it springs to mind almost daily when I read about global conflicts, as well. With young children, as with great nations, these conflicts are often about territory, property, or power. And so as early childhood educators, we invest in relationships, because we want to help children build skills for living in community.

But there’s another equally powerful reason that we focus on learning in relationship. We believe that the best and most interesting learning happens when children are thinking together, challenging each others’ theories, and offering up new, sometimes conflicting, understandings. This mode of peer-supported learning is sometimes called co-construction of knowledge, and is connected to the social constructivist theories of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Young children learn best when they learn through relationship.

But there’s another equally powerful reason that we focus on learning in relationship. We believe that the best and most interesting learning happens when children are thinking together, challenging each others’ theories, and offering up new, sometimes conflicting, understandings. This mode of peer-supported learning is sometimes called co-construction of knowledge, and is connected to the social constructivist theories of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Young children learn best when they learn through relationship.

And what about the grownups? Shouldn’t our learning as educators also be supported by opportunities to work and play together, examine and challenge each others’ thinking, and develop new realizations and theories as a result of our collaboration? How often do we make space to build theories together? Are we willing to get brave about listening carefully, possibly disagreeing, and pushing through to a new understanding?

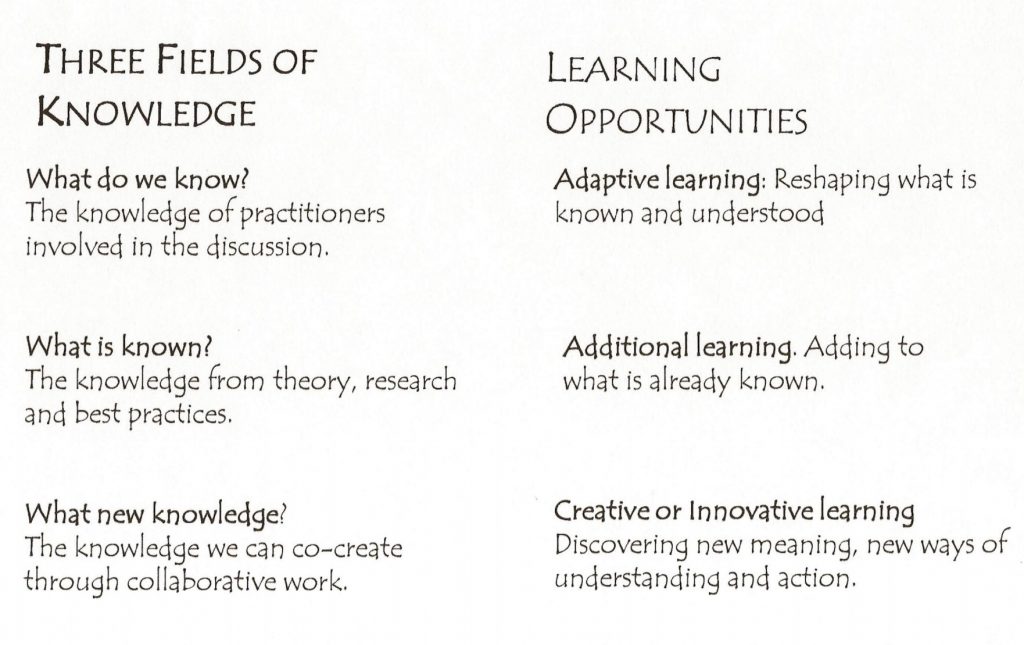

In their article Network Facilitation: The Power of Protocols, authors Karen Carter, Chris Cotton and Kirsten Hill suggest that there are three fields of knowledge that connect to specific types of learning. There’s what we already know from our own experience, there’s the information that is known from research in our field, and then there’s the new knowledge that we create together through collaboration. The authors suggest that these fields of knowledge correlate to different opportunities for learning: adaptive, additional, and – in the case of collaborative work – creative or innovative learning. And isn’t that the kind of learning we want to see happening, for both children and adults?

I was introduced to this notion by the authors of Reflecting in Communities of Practice, who suggest that there are 4 key structures we can put in place to support reflective, collaborative teaching and learning in early childhood programs:

I was introduced to this notion by the authors of Reflecting in Communities of Practice, who suggest that there are 4 key structures we can put in place to support reflective, collaborative teaching and learning in early childhood programs:

- dedicated and sufficient time for focused dialogue among educators

- intentional communities of practice that meet to discuss children’s work

- identified facilitators and critical friends to help deepen conversation

- commitment to using reflective protocols to help guide discussions

At an event that Hilltop hosted last month, Debbie Lebo and Wendy Cividanes, co-authors of the book, offered participants a day-long experience with all the components of this reflective model. We focused on honing our skills as reflective educators, and practiced bringing inquiry, intention, enthusiasm, and critical thinking to our work with children, families and each other.

And we’ll be continuing this conversation in May, with another full-day event focused on the practice and philosophy of Learning Stories. This session will be facilitated by Wendy Lee, Director of the Educational Leadership Project in Aotearoa New Zealand, where she helped establish Learning Stories as a national approach to assessment, part of the Te Whāriki Curriculum Framework. Wendy is the co-author of several books, including Learning Stories: Constructing Learner Identities in Early Education, and Understanding the Te Whāriki Approach: Early Years Education in Practice. You can learn more about Wendy’s work at http://www.elp.co.nz

Learning Stories are part of a philosophy for pedagogy and assessment, and an example of a reflective protocol to deepen thinking and encourage collaboration among adults. Grounded in socio-cultural theory and formative assessment, the Learning Story approach honors the child, family, teacher and community. Using Learning Stories, educators can write from the heart, in a way that engages children and families, while also integrating required assessment indicators. Learning Stories help educators consider previous experiences, outline new opportunities and possibilities, and bring their focus to delighting in children and participating in their learning. I hope you’ll be able to join Hilltop, and our event partner the Seattle Department of Education and Early Learning, for this discussion.

Learning Stories are part of a philosophy for pedagogy and assessment, and an example of a reflective protocol to deepen thinking and encourage collaboration among adults. Grounded in socio-cultural theory and formative assessment, the Learning Story approach honors the child, family, teacher and community. Using Learning Stories, educators can write from the heart, in a way that engages children and families, while also integrating required assessment indicators. Learning Stories help educators consider previous experiences, outline new opportunities and possibilities, and bring their focus to delighting in children and participating in their learning. I hope you’ll be able to join Hilltop, and our event partner the Seattle Department of Education and Early Learning, for this discussion.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://hilltopcc.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Sarah-Felstiner-photo-square.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Sarah Felstiner is the Curriculum Director at Hilltop Children’s Center, where she has worked since 1995.[/author_info] [/author]