White America (Almost) Stole My Soul

“Which part of you do you leave at the door in order to survive?” – Michael Browne (he/him), Community Engagement Manager at Hilltop

This question has made an impact in the way I think about my own identity. The first time I heard it out loud was on Episode Two (Deathmetal & Toddlers) on the podcast, Napcast, (Napcast is a podcast co-hosted by two male early childhood educators of color who so happen to by my colleagues at Hilltop, Nick Terrones (he/him) and Mike Browne (he/him)). The moment the question came up, I noticed that I listened with different ears. It resonated with me in such a way that I was instinctively listening with my whole being. When I say “I heard it out loud,” it was because I’ve heard this question many times in my head, but it has never taken concrete form like this, it used to just vaguely swim around in my head. Sometimes, it would become bigger and louder when I had to leave home to go to work for example, dictating some aspects of my routine like my clothes, hair, how to be and speak in a certain way, always hiding my Latin origins so I could survive in America.

During the podcast, I attentively listened to my colleagues’ answers to this question. They shared that they also leave part of their identities behind every day, to survive. Their vulnerability in that moment provoked a shift in me, almost as if I needed to hear those answers to validate my own thoughts about the forced identity process that so many of us go through. Why do I need that validation? It was like for the first time I had given myself permission to feel that way, too. That discomfort and pain really got to me, so I decided to sit with them for awhile.

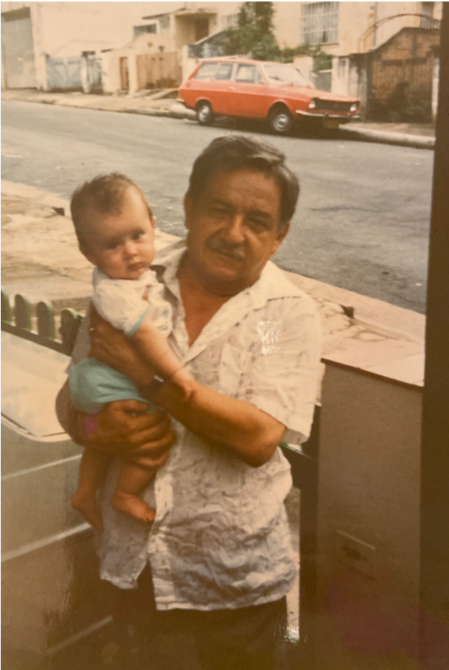

For the following days, I gave myself time to just think about some of my old and current memories that naturally made themselves present to me. Some of my old memories were about my time with my paternal grandparents, specifically my grandmother, who was a migrant just like my grandfather. She moved from an indigenous area in the north of Brazil called the Amazonas State, where a big part of the Amazon forest and indigenous tribes are situated. My grandmother and I were close, and I used to spend a lot of my time in her house growing up.

Just to give a bit of context, during the 19th century and beginning of 20th century, Brazil went through what we call “scientific racism” or racial whitening, an ideology based on the disappearance of the black race in Brazil through mixed breeding between white and black and indigenous people. This forced social order was structured and planned by the government to enforce the concept of “miscegenation” as something good and necessary: the whiter a person is, the better for the nation, since the population at that time was predominantly black and indigenous. This racist ideology happened through government violence on black and indigenous people, forced marriage between people of different skin colors and the start of European immigration to Brazil. All of these actions had one objective, the whitnening of the Brazilian population.

Going back to my grandparents: my grandmother was a fierce woman, and she would tell you to your face how things were, and point out loudly if she disagreed with something or someone, especially if injustice was happening. She also had her own oral traditions passed down for generations, and pride of being part of the First Nation People in Brazil. She thrived to keep that culture alive within her and her descendants. After getting married, my grandparents moved from Amazonas to Sao Paulo, a state in the south of Brazil with predominantly white people, where the racial whitening I described above was definitely the norm. They suffered racism for her dark skin color, accent, and indigenous culture. My dad was born during that time, in São Paulo, and to survive they all tried to hide who they were, to fit into this white point of view. But even trying very hard, they were still not welcomed.

I still have these memories of her: she had a twinkle in her eye whenever she would tell me stories about her life in the Amazon, and her mother’s life in the Kayapós tribe. She used to laugh when she remembered her times swimming in the Amazon river, sometimes with alligators and piranhas nearby. She really knew about the different kinds of animals, trees and fruits, and would tell me how they tasted and felt, and how to eat them. She told me about the Amazon Forest Spirit guardians, and how we should honor our Ancestors and our land. She absolutely loved her land. She wanted to make sure I wouldn’t forget that connection with our Ancestral roots, and she expected me to carry that legacy with me. These are some of my favorite memories of her.

I still have these memories of her: she had a twinkle in her eye whenever she would tell me stories about her life in the Amazon, and her mother’s life in the Kayapós tribe. She used to laugh when she remembered her times swimming in the Amazon river, sometimes with alligators and piranhas nearby. She really knew about the different kinds of animals, trees and fruits, and would tell me how they tasted and felt, and how to eat them. She told me about the Amazon Forest Spirit guardians, and how we should honor our Ancestors and our land. She absolutely loved her land. She wanted to make sure I wouldn’t forget that connection with our Ancestral roots, and she expected me to carry that legacy with me. These are some of my favorite memories of her.

At the same time, she would also tell me often how pretty I was, because I had light skin and light eyes. Some of my cousins didn’t get this appraisal – quite the contrary. I grew up with a reinforced notion from my own family, my mother and father included, that those physical attributes I had were desirable, and my dad’s and cousins’ skin colors and darker eyes were not so much. To this day, Brazil continues to reinforce the idea of whitening people’s descendants, impacting millions of families. It saddens me that I haven’t realized how steeped my family was in this belief, until now.

Revisiting these old memories then brought more recent memories to mind. In a very similar way, I started to trace a parallel between my current experience as a white or white-passing Latina in the US, and my grandparents’ and father’s trajectory in Brazil. Like my grandparents, I moved from a familiar place to an unfamiliar one. In my move from Brazil to America I came alone, with no family or friends, barely knowing the language. But I still had all that white privilege with me, so I wasn’t really alone after all.

When I think about my own privilege as a white-passing Latina in the US, and the privilege I had back in Brazil as a white woman, I see that I definitely carried some of the legacy my grandparents passed on to me, as well as all the whitening norms. However, after settling in a new territory, a new country, these white norms were challenged for the first time.

When I moved to America, one of the first things I realized was that it wasn’t safe for me to be Latina, specifically a Brazilian woman. More times that I can remember, me being full of life was misinterpreted and stereotyped as loud and angry, overly sexualized and seen as lacking intelligence due to language barriers. I realized that me being white in Brazil meant something different than being white here. So without noticing, I started changing. I watered down my personality: I shine a little less every day. I dimmed the possibilities for me to be who I was. I held tightly onto my white-passing privilege, so I could feel safe. I tried to change the way I speak, I tried not to code-switch, I tried to sound more “American.” Addressing a room full of people became something I was terrified of doing. “They will know I am different,” I thought. I no longer lived what my grandparents had taught me about our love for our land, for our people, for our stories and our great nation. I no longer felt I was holding that part of our history together. I changed my internal narratives so I could externally fit in.

My grandparents and my dad had to change in order for all of them to feel safe. They had to go through so many layers and narratives, daily, just so they could fit into the social contract society has forced on them. I can now make a connection with that, but it took so long. I had to move to a different country for that to happen. I am becoming more aware of the privilege I continue to hold, and the norms that are changing for me. I know that my other Brazilian compatriots, and Americans with dark skin, receive the full brunt of racism, here and in Brazil. I am learning how the social contract available for them is not the same for me, and it’s definitely not the same one I had back in Brazil.

My grandparents and my dad had to change in order for all of them to feel safe. They had to go through so many layers and narratives, daily, just so they could fit into the social contract society has forced on them. I can now make a connection with that, but it took so long. I had to move to a different country for that to happen. I am becoming more aware of the privilege I continue to hold, and the norms that are changing for me. I know that my other Brazilian compatriots, and Americans with dark skin, receive the full brunt of racism, here and in Brazil. I am learning how the social contract available for them is not the same for me, and it’s definitely not the same one I had back in Brazil.

Amidst these changes, I am holding onto what I think would honor my Ancestors. The ones I know, alive and deceased, and the ones that have been purposely forgotten by history. I am now listening to and reading the stories I grew up with, and I will try my best to pass them on. I also invest my time with Ancestral spiritual reparation work. I want to start wearing the clothes that represent different aspects of my people’s story. I am planning to visit my ancestor’s land, and continue to learn more about their history. I am working on speaking up, even if the words don’t make much sense in English, so I can be heard. I want to honor all of my ancestors by being full of life.

Now, I invite you to think about the impact of language, and space, and safety, on your own experiences:

Language barriers can happen in a multilayered way: are you listening through these barriers? Are you overpowering someone and/or finishing their sentences to “help” them? Are people around you being heard? Are you really thinking of them as intelligent, capable people? Do you slow down your talk purposely so you think others can understand you? Have you considered asking them first if they actually need that?

Thinking about the various spaces you occupy, how much space is occupied by people that don’t actually have a voice, and are invisible? Are you making space? Are you taking it away? In a workplace, taking the lead on a project or physically taking up space in a room are often not challenged by minorities – do you think their silence means that they are okay with this status quo? And if you could reimagine your relationships and the places you occupy, what would you do differently? How are you making space for other people to be full of life?

What assumptions do you still carry with you about safety? What does being safe mean to you? How do you change when fear is present? How much of your truth you are missing out on because you are not speaking up? Is there anything that you leave at the door every day, in order for you to fit into society?

Paty is an educator with 3-to-5 year olds at Hilltop Children’s Center where she has worked since 2017.

Hilltop Educator Institute collaborates regularly with change agents across North America, Europe and New Zealand to provide professional development opportunities in Greater Seattle through evening, half-day and full day workshops known as the Educator Discussion Series (EDS). Hilltop Educator Institute provides resources and support to educators, programs leaders, children’s advocates, and the community at large, in order to widen access and opportunity for all children. To study at Hilltop for a day, register for upcoming workshops, or learn more about our services, email Mike at institute@hilltopcc.org or visit us at www.hilltopcc.com/institute.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ admin_label=”section” _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row admin_label=”row” _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]