In Defense of Failure

by Jacob Leavitt, Educator, Hilltop Children’s Center

I am sitting in Hilltop’s conference room leafing through binders of In-Depth projects from the past two decades. These yearly projects take place in each classroom, with small groups lead by an individual teacher. The participating students are handpicked for their shared interests, personality dynamics, and developmental needs. They work together at regular intervals over the course of several months. The in-depths are emergent, child-centered, and more akin to lengthy investigations than planned projects. To me, the most inspirational of these stories start with a simple premise or hypothesis that gets turned on its head.

I see an example of this in a 2007 In-Depth project from Sunlight room. In it, a group of three to five-year-olds spent weeks and weeks exploring how a sink works. The kids began the project thinking that they knew the answer, and the teachers invited them, through long dialogues and studio sessions, to share and develop what were very, very incorrect assumptions. They sketched sinks and water fountains from all over the school. They played with sets of real plumbing pipes to explore the physical aspects of what they were discussing. These kids imagined desalinization machines hooked up to their sinks, underwater ferris wheels, oceanic waves that sent water to their taps. And do you think they ever figured out how a sink functions? Absolutely not! But they did use their imaginations, represented and re-represented their ideas, shared and listened, and learned about the scientific process. That last bit is key. Teaching in this manner harnesses the motivational power of children’s innate curiosity and gets them thinking scientifically about the world. This teacher let them practice exploration, rather than force them to learn about plumbing, and in that way they achieved success.

In another example, a teacher from Raindrop room engaged their two and three-year-old’s interest in all things scary. They did not take a particular stance nor imagine a singular goal. Instead, they gave the children a variety of opportunities to express their experience with scariness. The children told tales, acted as wild animals and monsters, made scary masks, and eventually journeyed out to the base of the Aurora bridge, where they presented the giant sculpted troll with handmade stick and rock cookies. The finale was an experience, not a product. At two and three, these kids were not ready to completely overcome their fear, and they certainly weren’t ready to catalog their experience and represent it to other people. Their experience was all about process, and the teacher allowed it to remain that way, thus honoring their developmental level.

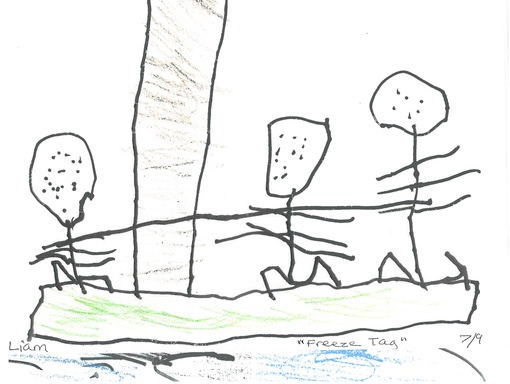

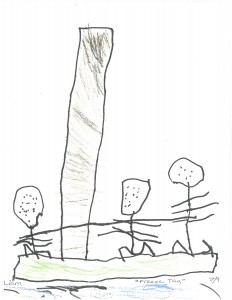

A recent In-depth from Mountain room began with an exploration of drama play. Reading through the notes, I see the project progress as the teacher notices that the children are struggling to find direction in their play. Handwritten notes taken during the sessions and in meetings with co-teachers detail all the questions that went through the teacher’s mind. Every “setback”, “upset”, or “confusion” was met with curiosity and a willingness to move forward. Little by little, the teacher guided the children in listening to each other and acknowledging each other’s leadership and ideas.. The kids lost themselves in all manner of expression – drawing, building, acting, games, storytelling – and through it gained invaluable social skills and confidence. Had the teacher stayed the original course, and not given such careful attention to the developmental level of those children, the experience would not have been nearly as meaningful.

In-depths are a perfect example of reflective practice enriching curriculum. The teacher must lead even though they don’t know where they are going. They supply the means, not the drive or the inspiration. If they think they know where they are going, then they must hope to be proven wrong, because by making an assumption, they have already closed their minds to many unpredictable experiences. What part of learning is better than surprise? You think you know something, and then you go a little deeper and, surprise! You had no idea. The work done in a successful, engaging in-depth is recursive, just like writing. You write a little, think back, and then you write some more.

Through patience, and a kind of aimlessness in regards to fact and product, we allow for the development of a more complete student – someone who will be better suited to approach confusion with curiosity and learn with pleasure. Doctor Lillian Katz, a former NAEYC president and researcher at the University of Illinois, emphasizes the difference between this and purely academic goals. She describes the latter as “concerned with the mastery of small discrete elements of disembodied information, usually related to pre-literacy skills in the early years, and practiced in drills, worksheets, and other kinds of exercises designed to prepare children for the next levels of literacy and numeracy learning.” But the new direction of Early Childhood Education, Hilltop’s direction anyway, is aimed at intellectual goals like reasoning, practicing the scientific method, forming creative ideas and running with those ideas until they lead somewhere.

This kind of work stimulates the young brain in ways clinging to factual knowledge can’t. That isn’t to say we don’t want to raise factual competent children, of course we do, but that sort of learning is best built on a strong intellectual disposition and a love of learning.

Most of us grew up with a more product-oriented education where our unrealistic answers were “incorrect”. If our project didn’t meet our original intentions, then it was a failure. From this perspective, it can be difficult to imagine taking on the most “serious” project of the year based on curiosity and a willingness to make missteps. It can be hard to explain to other adults why, as a teacher, we didn’t simply direct the children towards a more coherent, recognizable project. As difficult as it may be, we owe it to children to foster that spirit of inquiry. The key to engaging curious young minds seems to be accepting failure, embracing failure, then turning it into the opposite.

4 thoughts on “In Defense of Failure”

Comments are closed.

Thanks for wonderful insights into the children’s investigations, and the role of teachers across time. I’ll be bringing your post to our students’ notice – studying ECE.

What a wonderful reminder that “success” for teachers doesn’t mean you know where you are going as you undertake an investigation with children, but trust their eagerness and ability to engage in meaningful intellectual pursuits.

Thank you for reflecting back what we “know,” but neglect to say out loud. I so appreciate the depth of your own reflection and the inspiration it provides for all of us to keep listening, keep watching, keep learning from our children’s interests.

My biggest, best “failure ” as a teacher was bringing in a block of ice for the sensory table thinking it would be sensory play. But the children turned it into a clock and a calendar. “How long will it take to melt?’ was their big question so we kept track of it’s size and shape for days, putting it back into the freezer each night. There were many explorations as we watched, drew and photographed it until it was a tiny puddle.

On a sadder note, DEL says folk stories, folk tales, “Where The Wild Things Are” and “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” are violent so not allowed in any Early Achiever programs.