“Do you believe in Black Lives Matter?”

by Philip Kendall, Educator, Hilltop Children’s Center

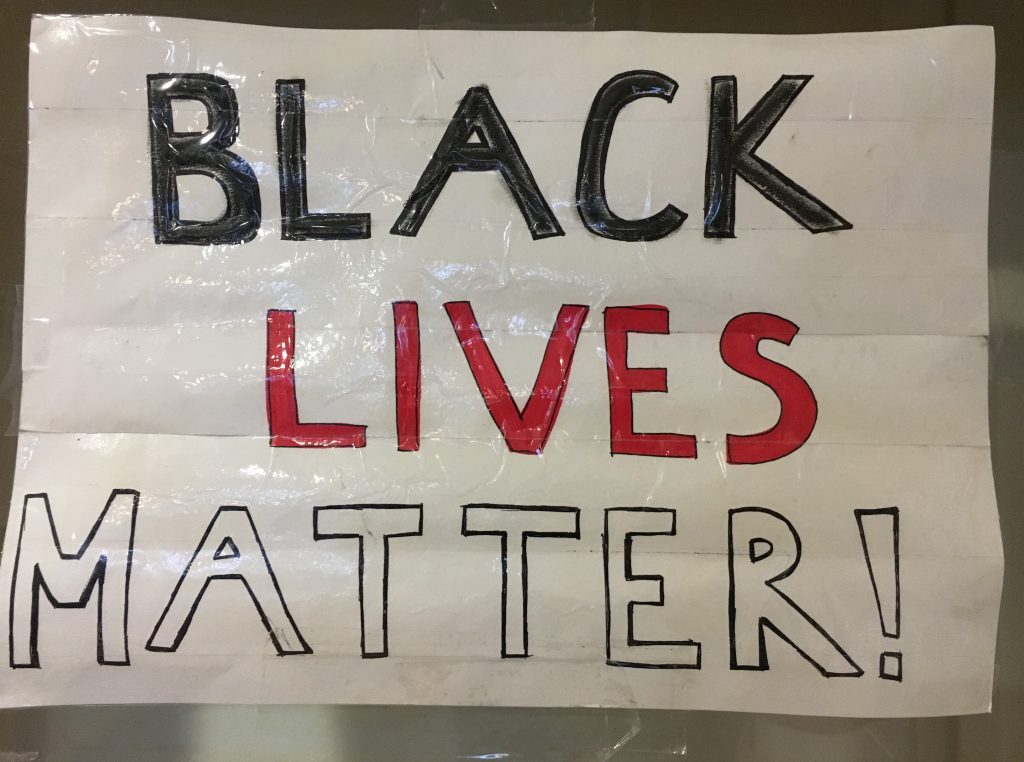

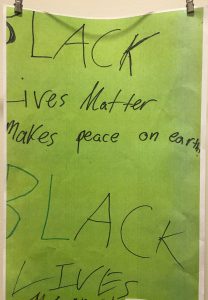

Students in Hilltop’s after-school program (ages 6-10) asked this question – of their teachers and their friends – repeatedly this year. Mostly those inquiring were black students. They had heard about Black Lives Matter on the news, and noticed how educators and students in our local Seattle Public Schools were supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. The kids were intrigued…they wanted to support the movement too, and wanted to know how Black Lives Matter was supported at Hilltop. They took action one afternoon by making their own Black Lives Matter signs.

Now what?

As educators in a school-age program trying to live out a child-led, Reggio-inspired, emergent curriculum, we wanted to be thoughtful about the way we engaged with this new politically-charged and fundamentally important student interest, especially because all the educators in this classroom are white. As is common practice at Hilltop, we offered a question back to the kids themselves: “What do you already know about Black Lives Matter?”

As educators in a school-age program trying to live out a child-led, Reggio-inspired, emergent curriculum, we wanted to be thoughtful about the way we engaged with this new politically-charged and fundamentally important student interest, especially because all the educators in this classroom are white. As is common practice at Hilltop, we offered a question back to the kids themselves: “What do you already know about Black Lives Matter?”

Responses varied, and many of them included similar information, including: “Well, black people were brought to America as slaves, and later Martin Luther King Jr. gave an ‘I Have a Dream Speech’ and he said that all people are equal, but some people still don’t agree, and so that’s why we have to say that black lives matter.”

At Hilltop, it is our ongoing practice to build curriculum around children’s questions and interests, and this seemed like a critical moment for just that kind of responsiveness. As educators in an emergent curriculum, we often find ourselves balancing our own knowledge and perspectives with the real-time information we’re receiving from the children, about the direction they want to take a topic or investigation. Personally, I struggled with wondering how much I should encourage these students to get more information to add to their understanding. I wanted the Big Kids to start a research project to learn more about African-American history, to learn more about the civil rights movement, and possibly to watch the #blacklivesmatter episode of the Truth and Power television series (available on Netflix). But I wondered what assumptions I might be making, as a white male educator with a research-centric perspective.

Before we put any of these plans in place – plans that might have overshadowed what mattered to the students – the children involved in this exploration had made plans of their own, and very quickly the BLM movement in Big Kids turned into one of the consistent favorite afterschool activities: a dramatic production. They wanted to put on a Black Lives Matter play! Their plan was to perform it in our indoor gym space, and to invite the whole school.

This was simultaneously exciting and nervous-making for our teaching team. It was clear that this idea had momentum, but often momentum can die out dazzlingly fast if teachers don’t provide the right support structures. Previous attempts at plays, fashion shows, gymnastics performances, and the like, had tended to end with frustration, arguments, and tears coming from one or several of the kids involved, due to conflicts about roles, changing rules, power dynamics, and so on. If this effort to produce a play ended badly – this most personal play, a production with a meaningful and important message – it could mean that our program wasn’t serving the children, and that the educators in the program weren’t good enough allies. With those concerns at stake, we wondered how we could help the students “pull this one off.”

This was simultaneously exciting and nervous-making for our teaching team. It was clear that this idea had momentum, but often momentum can die out dazzlingly fast if teachers don’t provide the right support structures. Previous attempts at plays, fashion shows, gymnastics performances, and the like, had tended to end with frustration, arguments, and tears coming from one or several of the kids involved, due to conflicts about roles, changing rules, power dynamics, and so on. If this effort to produce a play ended badly – this most personal play, a production with a meaningful and important message – it could mean that our program wasn’t serving the children, and that the educators in the program weren’t good enough allies. With those concerns at stake, we wondered how we could help the students “pull this one off.”

We wanted to do our best to keep the production as child-led as possible, but we did not want it to crash and burn, or to leave them stranded up there on stage. Educators assisted the production by setting up some structures for success: helping choose a date, helping hang up the flyers they had made, re-directing them to stay on task, note taking, sending out a school wide invitation, and setting up the stage. But the bulk of the work – the plot, the characters, the props, the costume ideas, the set, the programming, and most of the “marketing” – all came from the kids. They worked together on this over the course of a few weeks: they argued, they goofed around, they stressed, and then they performed. Below is a brief synopsis of their play:

[box] The show starts with each player introducing themselves, announcing which character(s) they will portray in the play, reading an inspirational quote, and sharing something about their own developing understanding of their cultural and/or ethnic heritage.

“My name is Hallie. I’m black. In this play I’m the teacher, and I was also the director.”

“My name is Hans. I’m white, and one of my religions is German.”

“My name is Karen. I’m one of the students in the play. My family is from Russia.”

The first scene of the play is set in a classroom, where two new students from Ethiopia are introduced for the first time. The other kids in the class laugh at the students’ names. The teasing continues at lunch-time with hurtful nicknames:

“Is your name really Luom? Are you sure it isn’t Poo-um?!”

and making fun of the students’ hair. The Ethiopian students run off crying. Another student (who is white) is sitting with the new students at lunch and sticks up for them.

“Hey. You shouldn’t say things like that. That’s rude.”

“Well, why are you even sitting with them? I mean, they’re black!”

“Because they’re my friends. I’m going to tell a teacher.”

The students are called in to the principal’s office to have a talk. The principal asks the antagonist kids if what she had heard was true, and the students confess to picking on the new students of color. Then the principal tells them,

“That’s not ok. I don’t want to hear about this happening again. I don’t want to have to call your parents.”

The students all respond:

“Ok, we understand”

The last scene is a phone call, in which the antagonistic students call the students of color to apologize, then invite them to a birthday party. The apology and invitation are accepted, and all of the kids go to the party as friends. The end. [/box]

A simple play. Not a very nuanced play. But the messages the kids wanted to convey were powerful:

- No bullying.

- Stick up for your friends.

- Ask for help.

- Black Lives Matter.

Most everyone in the school came to the show, including many parents and family members, and it went off without any major hitches. I could sense the pride that the kids felt after performing, as they did cartwheels and sang while sweeping up the popcorn that had been dropped on the ground by the audience. I imagine the kids were proud of themselves for completing a large project and sharing the results with a large audience.

Even if the play hadn’t turned out to be “a success,” I believe the idea to have the play and the meaning behind the play was already a huge success in and of itself. What resulted was not so much a historical/factual undertaking, but more of a process of self-identification, racial/ethnic difference processing, an anti-bullying campaign, and a choice by these children to bring a public focus to their experiences as black children and children of recently-immigrated families. This play allowed the students a platform – a place to stand up and assert their identities, and to pre-emptively stick up for themselves and their right to fair treatment at our center, at their elementary schools, and in the community at large.

Even if the play hadn’t turned out to be “a success,” I believe the idea to have the play and the meaning behind the play was already a huge success in and of itself. What resulted was not so much a historical/factual undertaking, but more of a process of self-identification, racial/ethnic difference processing, an anti-bullying campaign, and a choice by these children to bring a public focus to their experiences as black children and children of recently-immigrated families. This play allowed the students a platform – a place to stand up and assert their identities, and to pre-emptively stick up for themselves and their right to fair treatment at our center, at their elementary schools, and in the community at large.

Since the performance of this play, the students have come up with other production ideas that continue to flesh out themes of identity and difference. One play included lots of role swapping – multiple kids taking turns playing the same character, alternate worlds, and “good” and “evil” versions of specific characters, as well. In a school lunch scene of that play, there was a group of “mean kids” and a group of “nice kids,” grouped together irrespective of race. The main character was called “Normal Girl,” and it was her job to save the world.

How have you and your colleagues responded to children’s questions about challenging ideas, about topics from the headlines, or about race in particular?

How have you supported children’s initiative in expressing and developing their understanding of these topics?

How might the children, families, and educators in your program respond to the Big Kids’ question:

“Do you believe in Black Lives Matter?”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://hilltopcc.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Phillip.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Philip Kendall is an educator with 6-10 year olds at Hilltop Children’s Center, where he has worked since 2014.[/author_info] [/author]